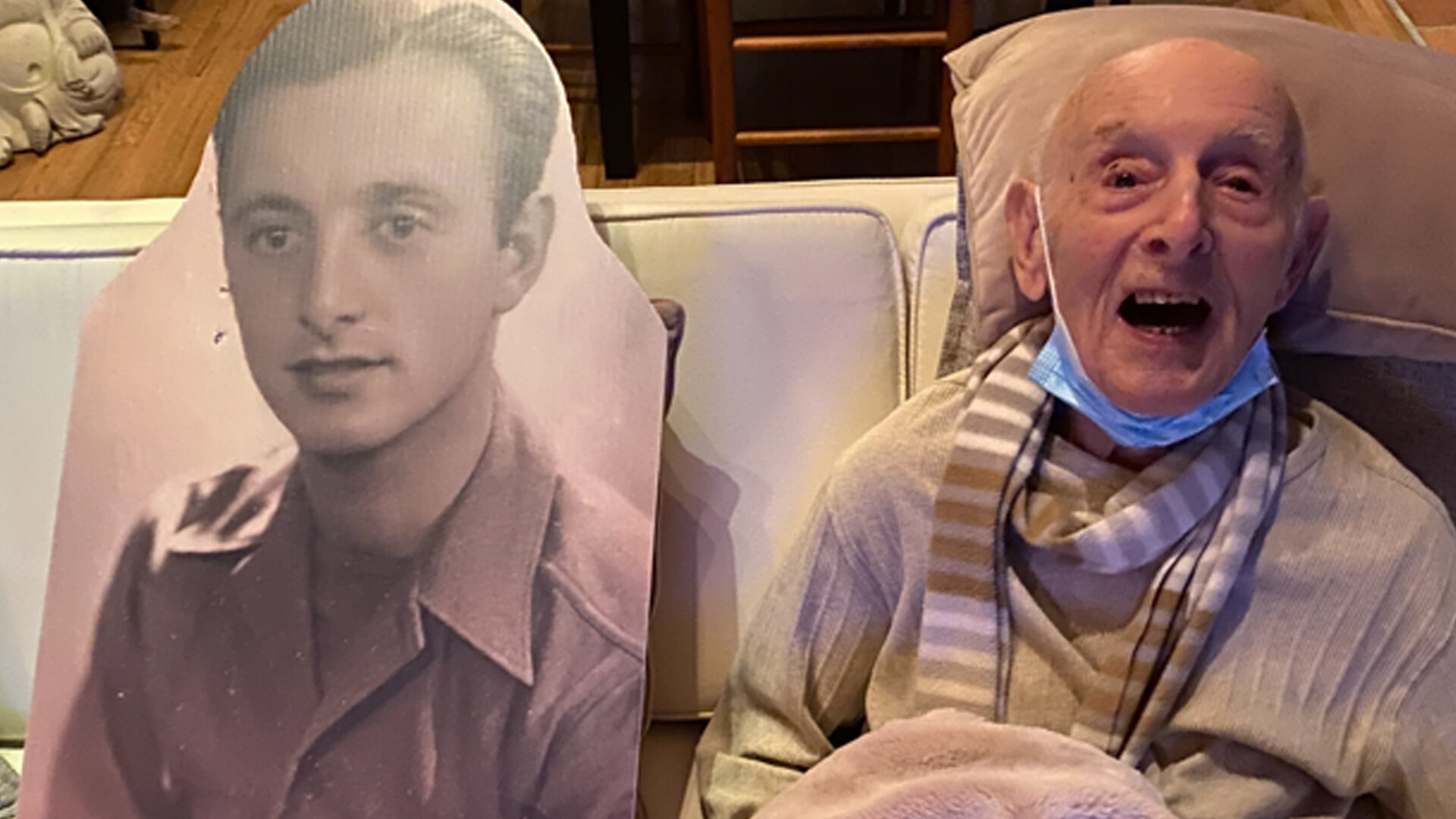

Irving G. Brown - U.S. Army 1943-46

Irving G. Brown - U.S. Army 1943-46

Irving G. Brown from The Bronx, NY passed away January 18, 2021. Irving served with the Army Medical Corps during WWII. Irving was assigned to the 671st Medical Regiment stationed in the northern Apennine Mountains and the Po Valley. When the American troops broke through the German lines north of Bologna Irving saw action. In the collection company he, along with three or four other medics, performed first aid on the troops and mainly tried to stop any bleeding. To stop the bleeding they bandaged the wounded and/or applied tourniquets. If men were ripped apart as Irving said, more seriously wounded with stomach wounds for instance, they were injected with morphine to kill the pain until they could be treated. The wounded were then picked up and taken to an ambulance which drove them back to the evacuation hospital. From the collection company the wounded were transported to a clearing company, generally within twenty miles from the front.

According to Irving's daughter-in-law Ann Brown, "He was in the hospital for a heart procedure and caught COVID while there. It was a difficult period of time. He is at peace now."

This interview was recorded over ZOOM during the Spring of 2020

Irving’s brother Leo Brown was killed in action on November 12th, 1944. Leo had been in the Army Air Corps and was on a ship below deck sitting at a table playing cards when the ship was struck by a Japanese kamikaze pilot. Half the men at the table were killed while the others survived. Leo was one of the unlucky ones. Irving took photographs of the Star of David marking his brother’s grave. The Graves Registration soldier was bothered by the Star of David and, because Leo’s name was Brown, asked Irving if he was correctly buried. Irving acknowledged that Leo was Jewish. Eventually, in the 1950s the family had Leo’s body returned home and a ceremony was held for Leo. Today Leo is buried with his parents in Mount Zion cemetery in New York .

Irving G. Brown’s Military Experiences

It was June 1943, in the middle of World War II. Irving G. Brown, my uncle, graduated from James Monroe High School in the Bronx, New York. The war was not going well for the Allies and most young men expected to be drafted. Irving was born on April 27, 1925, and it was his luck to be eighteen years old, an ideal draft age. He waited to be drafted.

Once out of high school and while waiting to receive a draft notice, Irving needed to get a job to help out his family. They, along with other American families, had survived the Great Depression. His family included father Martin, mother Rose, older brothers Sam, my father, and Leo, and younger brother Edward. They lived at 1505 Charlotte Street in the Bronx, in a working class Jewish neighborhood. Sam and Leo had already been inducted and were training in the U.S. before deployment overseas. Sam eventually went to Europe while Leo was stationed in the Pacific. The family could use all the financial help it could get.

Irving got a job at the U.S. Post Office right after he graduated in June. He was hired as a temporary clerk and letter carrier. As part of his job, he would run specials, deliver and sort the mail. He was also used as a replacement for other postal workers who were out on vacation or sick. Irving was paid forty cents an hour, which for forty hours totaled sixteen dollars a week, not great money but every bit helped. Irving told me that he thanked the labor movement for negotiating higher wages for union workers, which increased wages for non-union workers such as Irving as well. Being a dutiful son, Irving turned over most of his paycheck to his parents. Rose opened up his first bank account at Bronx Savings Bank (today named the Apple Bank) and put his wages in it for Irving. Irving would also run specials, special deliveries, and the customers often tipped him. He usually received five cents for each special deliver but he remembered a time when he got a whopping quarter – life was good.

That summer Irving received a notice to report for a pre-induction physical at 384 E. 149th Street in the Bronx. He had to pass it because he was inducted on September 14, 1943 in the old Grand Central Palace next to Manhattan’s Grand Central Station. On October 5, 1943, Irving was sent to a reception center in Camp Upton, Yaphank, Long Island, New York. Irving was introduced to Army life on his first day at Camp Upton when he was assigned KP (Kitchen Patrol) duty. Then the Army, in its infinite wisdom, apparently realized Irving’s real ability and assigned him to clean out open air latrines with a shovel. He shoveled the contents of the latrines to a long canal where it fermented and was eventually trucked away to be used as fertilizer. After two or three days of latrine duty, Irving was sent to Basic Training in Camp Barkley, Texas, near Abilene. He spent seventeen weeks learning how to drill, march, shoot and become a soldier.

Upon completing Basic Training, Irving was assigned to the Army Medical Corps and sent to O’Reilly General Hospital in Springfield, Missouri. He spent three months there as a Medical Technician and was promoted to a PFC (Private First Class). While at O’Reilly, Irving took classes in materia medica. He learned about drugs and how to compound them, and he frequently administered the Army’s standard APC capsules to GIs. Irving also assisted with two actual autopsies of soldiers, one of whom drowned while the other died of an overdose of Sulphur pills given him to cure gonorrhea. Irving felt the overdose in particular to be a tragedy since the young soldier had received a prescription for a specific number of Sulphur pills yet he took many more than prescribed apparently thinking that he could be cured faster. Irving learned a lifelong lesson from that experience: to follow the doctor’s prescription exactly. He performed other duties at the hospital and helped soldiers recuperating from wounds, malaria and dysentery. After four months at O’Reilly General Hospital, in April 1944, Irving was sent to a personnel replacement depot at Camp Shenango in northwestern Pennsylvania for deployment overseas. At the camp he met a soldier he knew from his neighborhood in the Bronx by the name was Al Garfinkle. Al was the brother of Irving’s friend and classmate Murray Garfinkle. Al was stationed at Camp Shenango and knew that Irving was only eighteen years old. He also knew about a recent Army ruling that anyone under the age of twenty, especially non-combatants, was not supposed to be shipped out at that time. They were to remain in the U.S. until they reached the twenty years of age. Al had some influence and was able to get Irving assigned to and trained in the Medical Dispensary at Camp Shenango. There Irving assisted in giving injections to new recruits. It was great duty. He was able to go on leave and visit nearby cities such as Youngstown, Ohio, Meadville and Erie, Pennsylvania. However, it was very cold in northwestern Pennsylvania during the winter. On the coldest day of the winter, Irving’s luck ran out and he was assigned guard duty at a motor pool on Lake Erie. As part of his duty he had to ensure that the potbellied stoves worked so that the troops in the Quonset huts didn’t freeze, which he did. However, although he wore a parka and fur lined boots he almost froze.

For some unknown reason, from Camp Shenango Irving was sent back to Camp Barkley, Texas for seventeen more weeks of Basic Training; the same training that he had previously received. Irving joked to me that he must have done so well in Basic that the Army wanted him to go through it again. In early 1945, upon the second successful completion of Basic Training, Irving was sent to Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania for a couple of weeks then to Newport News, Virginia, his Port of Embarkation overseas.

Irving arrived in Norfolk in the evening and the troops boarded the troop transport USS Mariposa the next morning. The transport had been an ocean liner that had traveled between Los Angeles, California and Honolulu, Hawaii. However, it, along with many others during the war, was a thirty day wonder, converted into a transport to carry troops across the ocean. The room Irving slept in had five tiers of canvass hammocks, one on top of the other, in metal frames. The canvass could be pulled up when no one was on them and down at night for the men to sleep. There were approximately eighty to one hundred men in Irving’s room, which was either the second or third deck below the top. The Mariposa zig zagged across the ocean to avoid German U boats. It varied its pattern, going two miles or so in one direction and then cutting back two miles in the other direction. The ship took approximately two weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean and the troops became extremely bored. The Army didn’t have a lot for the troops to do while on the ship. Sometimes they did calisthenics. Other times, Irving would go top side and read or go to the rear of the boat to watch its wake. When the weather got rough crossing the Atlantic the troops could hear the ship creaking. Navy food was not what it was cracked up to be. Irving remembers eating a great deal of oatmeal, farina, grits and eggs. Irving was again assigned KP duty on the ship; perhaps the Army recognized his excellent service doing the same at Camp Upton.

The USS Mariposa reached the Mediterranean Ocean, past the Rock of Gibraltar and docked at Oran, Algeria for a day or two to re-fuel and re-supply. The troops were not permitted to get off of the ship in that port. The Mariposa finally arrived in the port of Naples, Italy only to find that the Germans had sunk many vessels and mined the harbor. The harbor was full of masts of half sunken ships, which the transport had to skirt around. It also had to avoid the mines. Many other ships crowded the harbor and it took two days to unload the ship. The troops reached land in landing boats, which could maneuver through the wrecks much easier than the large transport.

From Naples, Irving was sent to a replacement depot in Caserta, Italy a short distance away. He then went to a large replacement depot in Florence where he was assigned to be a litter bearer in a collecting company in the 671st Medical Regiment, which was part of the US 5th Army. Among the other positions in the collecting company were medical technicians, medical aides, and the ambulance corps. Shortly after Irving was assigned to the 671st Medical Regiment, the troops were called together by a colonel who announced “President Roosevelt passed away”. The men were stunned and some, including Irving, shed a few tears. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and had been president since March of 1933, during most of the lifetime of these young soldiers. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was the only president that many of these men had ever known. His death was a great loss to them.

Irving’s unit was transported to northern Italy. They were stationed in the northern Apennine Mountains and the Po Valley. When the American troops broke through the German lines north of Bologna Irving saw action for about a week. In the collection company he, along with three or four other medics, performed first aid on the troops and mainly tried to stop any bleeding. To stop the bleeding they bandaged the wounded and/or applied tourniquets. If men were ripped apart as Irving said, more seriously wounded with stomach wounds for instance, they were injected with morphine to kill the pain until they could be treated. The wounded were then picked up and taken to an ambulance which drove them back to the evacuation hospital. From the collection company the wounded were transported to a clearing company, generally within twenty miles from the front. If men were killed all the medics could do was cover them with a sheet and try to make sure that their dog tags or some other form of identification was visible for Graves Registration.

Irving was on the front lines near the end of the war and the Germans couldn’t get supplies so he recalled that there was not much fighting. There was, however, the mass surrender of many German troops. Irving remembers hundreds of German soldiers coming down from the mountains to surrender. When they did surrender the Infantry confiscated not only their weapons and military equipment but often liberated their personal equipment, money, cameras, etc. Irving recalls seeing barracks bags full of German booty.

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, about one month after Irving arrived in Italy. When the war in Europe ended, Irving was sent back to Florence and then reassigned to Leghorn from May until July. In Leghorn he was assigned to an evacuation hospital but there was not much to do. Irving was able to get passes and travel throughout Italy. Irving met his cousin Leo Rief who was stationed north of Verona in an antiaircraft unit. Leo had tried to become a pilot but became sick when he flew in the air and wasn’t able to do so. The Army then assigned him to an antiaircraft unit. Irving went all over northern Italy, from Verona to Bologna to Venice where he spent three days on the beach. He and some buddies were able to hitch rides on military planes throughout Italy. They got a ride on a B 25 from Leghorn to Naples where they stayed a few days and returned on a P 38 fighter plane.

Since the war in Europe was over the troops were waiting to go home. Some veterans had been in for over two years, from North Africa to Sicily up to northern Italy. They were very anxious to go home. However, the war in the Pacific continued. Irving’s unit shipped out from Leghorn on route to the Pacific on the USS Marine Dragon. They traveled passed Gibraltar, which was very imposing. It took three weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean, go through the Caribbean Sea and arrive at Panama City, Panama. As they traversed the Panama Canal they began to hear rumors that something had happened. The ship needed repairs and remained in Panama City for two days. While repairs were being made, the troops were called together and told that the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Japan. The officer said that the war would be over in a few days. He said we got the bomb and that was good news for us. Nobody knew what was going on. They weren’t sure if the troops were going to go home or become part of the army of occupation. Soldiers from the west coast who were closest to their homes wanted to go home; they felt that they fought the Germans and didn’t want to fight the Japanese as well. They were not happy that they were not able to return home. The Marine Dragon stayed in Panama for about one week and then go the word that it was going to New Guinea. The ship entered Gulog Harbor in northern New Guinea for re-fueling and re-supplies but the refrigeration system broke down. The frozen food spoiled and had to be thrown overboard. Irving remembers the sharks going after the spoiled food. Once the refrigeration system was repaired, the ship continued on to the Philippines. The war with the Japanese was still on going so the Marine Dragon zig zagging as it sailed to avoid an attack by Japanese submarines. The Marine Dragon and its GI cargo finally reached their destination of Manila in the Philippines. It had been 54 days since the ship left Leghorn, Italy and the soldiers had remained on board the entire time. Most of their meals consisted of C rations and K rations. They were anxious to get on land.

Irving was assigned to the military hospital in Manila. Within two months’ time, most of his unit was sent home, leaving Irving and two others as the last replacements. They lived in a bamboo Quonset hut in a room that could hold forty troops. While in Manila, Irving learned from correspondence home of the location of another cousin, Sonny Rudick. Sonny was in Manila being treated for malaria. Irving and Sonny explored Manila together. Irving also went on leave to Corregidor Island, the scene of the U.S. surrender of the Philippines. In addition, he visited Leyte, which was of great significance to him since his brother Leo had been killed there on November 12, 1944, and was buried in the American cemetery located there. Leo had been in the Army Air Corps and was on a ship below deck sitting at a table playing cards when the ship was struck by a Japanese kamikaze pilot. Half the men at the table were killed while the others survived. Leo was one of the unlucky ones. Irving took photographs of the Star of David marking his brother’s grave. The Graves Registration soldier was bothered by the Star of David and, because Leo’s name was Brown, asked Irving if he was correctly buried. Irving acknowledged that Leo was Jewish. Eventually, in the 1950s the family had Leo’s body returned home and a ceremony was held for Leo. Today Leo is buried with his parents in Mount Zion cemetery in New York.

Irving remained stationed in the Philippines until March of 1946 when he got the word that he was going home. Just before he left, a typhoon hit Manila and did significant damage to the port along with the Navy ships docked in the harbor. About sixty ships were damaged, including battle ships, cruisers and destroyers. Some ships were sunk and a few lives were lost. The typhoon delayed Irving going home for a few weeks. After the storm, Irving boarded another troop ship to return home. The time the ship didn’t have to zig zag to avoid submarines so it only took two weeks to cross the Pacific Ocean. The troop ship went to San Francisco and as it was approaching it passed the prison on Alcatraz Island. Prisoners held up make shift signs saying: “Good Job”, “Well Done”, and “Welcome Home”. The ship docked in San Francisco and Irving was sent to Camp Stoneman for one day then the troops boarded a train that took them slowly across the country. For five days the train made its way through the U.S., from the Rocky Mountains to the plains states to the east coast. The soldiers were assigned to rooms with canvas bunks that contained three tiers this time. When it was meal time they took their mess kits and went to the dining car where they received their food and brought it back to the small room to eat. They finally arrived at the separation center in Fort Dix, New Jersey, where Irving was received an Honorable Discharge on April 6, 1946, as a Technician Fifth Grade. Since he served in the European war zone during combat, Irving was eligible to receive the European, Middle Eastern and North African Campaign medal, the PO Valley Campaign medal with a battle star and the North Apennine Campaign medal with a battle star. He was also eligible for the Philippine, Asia and Pacific Campaign medal. He received all of them except for the North Apennine Campaign medal because the Army ran out of the medals at that time.

From Fort Dix Irving took a train home to New York City where he was reunited with family. Irving got his first post war job as an accountant for $25.00 a week and went on to live a productive and fruitful life.

Sources:

Irving G. Brown, interviewed by Jeff Brown, July 11, July 25 and September 10, 2015.